Arguably the most famous and consequential travel narrative, Christopher Columbus’s report of his first voyage and his ‘discovery’ of several islands (he made landfall in the Bahamas) not only marks the start of the age of colonial exploration but also demonstrates the extensive power of the emerging print medium for quickly disseminating news from around the world and creating a shared present for the cultural centres of early modern Europe.

Upon his return in March 1493, Columbus posted a letter (written while still on board the Niña) addressed to the Spanish courtier Luis de Santángel who had been instrumental in supporting the voyage. The document was quickly translated into several languages and published in various editions across Europe within the next few months, making it a bestseller of the early print culture. It contains information on the people he encountered (described as handsome, timorous yet acutely intelligent) and on the economic possibilities of the various islands rich in spices, gold mines and fertile fields.

The contents of another letter, sent to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain, were lost until 1989 when a transcription of a 16th-century manuscript, including a copy of the letter, was published as Libro copiador de Cristóbal Colón. The letters differ in important ways: For instance, the published letter seems to be deliberately vague about the precise location of the islands described, probably in an effort to put potential rival explorers off the scent. An earlier letter, written during a terrible storm, was wrapped in cloth and thrown into the sea in a barrel to guard against the possibility of news of the voyage being lost with the ship. It never arrived.

SUB Göttingen holds two distinct editions of the published Columbus letter.

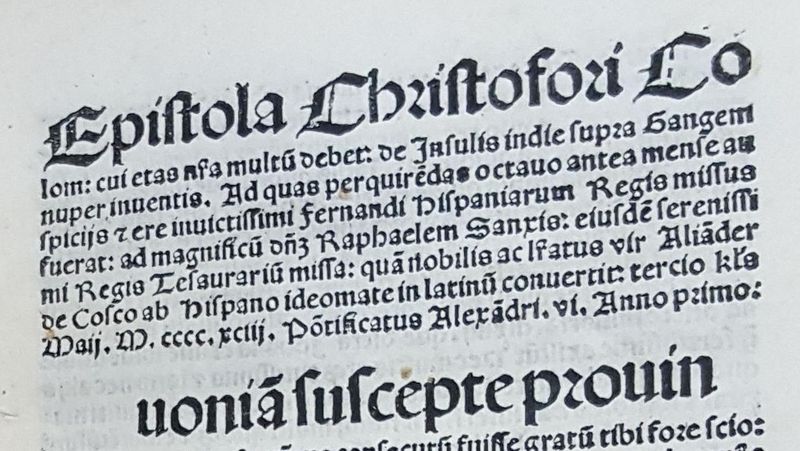

1. Columbus, Christophorus. Epistola de insulis nuper inventis (Latin, tr. by Leandro di Cosco, 29 Apr. 1493). Paris: In campo Gaillardi (Guy Marchant), [after 29 Apr. 1493]. ISTC ic00761000; GW 7175; Kind (Göttingen) 813 (A); 8 H AM I, 502 INC RARA.

The Göttingen copy belongs to the earliest of the Paris editions of the Latin translation printed in 1493 by Guy Marchant. Unlike the other Paris editions it does not contain a woodcut and the title is phrased slightly differently (Epistola de insulis repertis de novo). The only other known copy of this edition is held at the Royal Library of Turin. You can view the digitized version of the Göttingen copy here.

2. Verardus, Carolus. Historia Baetica. Add: Christophorus Columbus: De insulis nuper in mare Indico repertis. [Basel]: J[ohann] B[ergmann de Olpe], 1494. ISTC iv00125000; GW M49579; Kind (Göttingen) 849; 8 TH IREN 12/10 (3) INC.

The Basle edition of 1494 is characterized by several detailed woodcut illustrations, some of which were recycled and recontextualized from earlier works. It was published together with a history of the conquest of Granada, written by Carolus Verardus.

Like other forms of colonial writing, Columbus’s letter is a political performance driven by various agendas such as the need to secure further funding for a second voyage to what he still believed were the outer reaches of Asia. The letter not only became a template for other reports of exploration but – as part of the growing colonial discourse – also influenced literary works, especially through its memorable descriptions of the looks and habits of a strange people living in a New World.

Shakespeare’s The Tempest has been linked to accounts of the New World since the 19th century, yet attitudes towards Prospero, as towards Columbus, have changed significantly in the last few decades. Critics have increasingly focused on The Tempest’s topicality and complex staging of the colonial encounter and analysed the play within the theoretical frameworks of New Historicism and Postcolonial Studies, focusing on the power relations between the European and native characters (Caliban and Ariel).

When Caliban asks the drunken butler Stephano “Hast thou not dropped from the heaven?” it is tempting to read this as a direct allusion to – if not parody of – Columbus’s report of the natives’ response to the arrival of the Spaniards: “They do not hold any creed nor are they idolaters; only they all believe that power and good are in the heavens and are very firmly convinced that I, with these ships and men, came from the heavens, and in this belief they everywhere received me after they had mastered their fear.”

While the language of exploration and conquest of the early modern period often made use of sexual imagery by depicting America and other ‘virgin lands’ as desirable women, John Donne uses the theme of colonial discovery as one the central (bawdy) conceits in his Elegy XIX “To His Mistress Going to Bed”:

O my America! My new-found-land,

My kingdom, safeliest when with one man manned,

My mine of precious stones! My empery!

How blessed am I in this discovering thee!

(Unlike Columbus's letter and despite the growing importance of print culture in Tudor England, Donne’s poetic work was circulated in manuscript form among friends and only published posthumously. SUB Göttingen owns the 1633 first edition of Donne's poems as well as the 1669 edition which first included Elegy XIX, deemed too indecent by the earlier publisher:)

As Donne’s poem reveals, the thrill of exploration and dis-covery also carries the shadow of dominance and exploitation, both economic and sexual. Protests around Columbus Day celebrations in the United States have been growing over the last years. Recently, Los Angeles has become the latest city to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

Further Reading

The website of the Osher Map Library offers information on the Basle 1494 edition and on the rapid dissemination of the various edition of the Columbus letter throughout Europe.

Read Cecil Jane's English translation of the letter which is quoted above.

On his TV show Last Week Tonight, John Oliver asked in 2014: "Columbus Day - How Is This Still a Thing?"

Chiappelli, Fredi, ed. First Images of America: The Impact of the New World on the Old. 2 vols. Berkeley, CA: U of California P, 1976. [SUB library catalogue entry]

Greenblatt, Stephen. Learning to Curse: Essays in Early Modern Culture. New York, NY: Routledge, 2007. Routledge Classics. [SUB library catalogue entry]

Harrisse, Henry: "The Early Paris Editions of Columbus’s First 'Epistola'." Zentralblatt für Bibliothekswesen 1893, 3: 118-121. [read it online]

Hart, Jonathan. Columbus, Shakespeare and the Interpretation of the New World. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. [SUB library catalogue entry]

Young, R.V.: "'O My America, My New-Found-Land’: Pornography and Imperial Politics in Donne's Elegies." South Central Review 4, 2 (1987): 35-48. https://doi.org/10.2307/3189162

Zamora, Margarita. Reading Columbus. Berkeley: U of California P, 1993. [SUB library catalogue entry]